发展项目, 亚洲其他地区2014年2月25日

Mekong farmers and farm women: Participation, gender and appropriate technology

陈美玲

陳美玲於1993年加入樂施會,2005年離職。在職期間,曾專責香港樂施會中國項目部以及國際項目部的發展項目設計、策略及擴展等工作。2013年,美玲重返樂施會,目前爲國際項目總監。

By Mayling Chan — International Programme Director

Sustainable agriculture can be crudely described as a way of farming that attempts to minimise the use of external industrial materials while maximising that of materials which are available on the farm. Because urbanisation brings many people to towns and cities to find jobs in factories, a shortage in farming labour is a worldwide problem. Without sufficient labour, farmers cannot grow green manure, which are plants sown to improve soil fertility. They also cannot make compost, collect and transport animal manure, manage pests, cultivate crops, or even sell and market their products. This is an obvious disadvantage to sustainable farming.

Sustainable farming is tremendously diverse but should be sufficiently inclusive to make the most of local resources. Contrary to what many people think, sustainable farming does not necessarily mean organic farming or cutting out chemical fertilisers. Some farming methods are more sustainable than the current, highly industrialised agriculture model, which ignores the costs to nature. One method cuts down on industrial fertilisers while increasing the use of manure and compost. Another method uses fertilisers in a more efficient and effective manner. Therefore, when discussing sustainable farming, we need to be specific about the context. Sustainable farming can create a win-win situation that benefits both people in need and the natural environment, which is under the threat of climate change. To explore how it can have the greatest impact, we need to look at how it works in each individual situation.

In the Mekong region in Cambodia, farmers have increasingly been using the system of rice intensification, or SRI and 单株种植, which Oxfam has adapted. This system has been observed, researched and developed for more than five decades and now can be adapted for rainfed agriculture as well as irrigated fields in Asia. It is one kind of appropriate technology that tries to improve yield with effective water management, and make farming less fertiliser- and labour-intensive compared to the traditional way of transplanting, which is the process of moving plants from one location to another. Farmers are curious to find out how it works by doing it. Since seeing could lead to believing, sharing and solidarity between farmers and farm women in the fields can promote a sense of learning that takes into account everybody’s pace and needs.

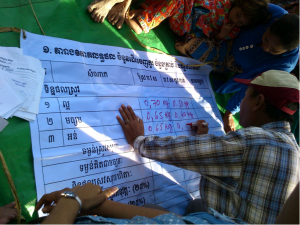

With a spirit of camaraderie, farmers and farm women experiment, learn and prove scientifically the strengths and weaknesses of different ways of planting rice on a field in Cambodia. The farm women found that planting rice seedlings farther apart provides higher yields. Scientific research does not just happen in universities and classrooms.

Scientific data are not only generated in labs at universities, but also by farmers and farm women in the fields.

In one particular learning and sharing session which I saw in Cambodia, women could come with their children. The kids formed an automatic play group, leaving the women free to join in without worrying. They took farming instruments in their hands and participated actively in the experiment, testing the strength of different ways of farming. They harvested rice from small, square plots on a field which had been planted using two different methods: random transplanting and well-spaced transplanting. They got hold of the rice stalks, took out the rice pellets, then counted and weighed them. Then, they shared and compared the results. It was as simple as that!

In Madagascar, thanks to this rice cultivation method, the yield is now four times what it used to be, at 2 tonnes per hectare.

But this does not mean that we have to strictly adopt SRI in every situation. Farmers, agriculturalists, NGOs and institutes have to try it out and see for themselves. Take, for example, one old farmer I met. He told me: “I am alone in my household. There is no one else to work with me to plant the seedlings in nicely spaced lines the way my other friends do.”

Oxfam staff Thakur from Nepal and Kabir from Bangldesh discuss the challenges of the appropriate technology to adopt with partners in Cambodia.

Our colleagues in Nepal and Bangladesh have learned the prinicples of SRI and are now comparing different adaptations of this method in the countries where they are working. In the Asia region, people practice a kind of sustainable farming which is similar to SRI, but which is not limited to SRI techniques. This is the beauty of learning the principles of an appropriate technology and applying it to different conditions. If the results are not as good as expected, farmers and farm women can just adjust the method with collective wisdom.

Check out a clip created by Oxfam Australia Active Citizenship Manager Stuart Thomson about the work that Oxfam and its partner Rachana are doing to promote SRI:

Note:

SRI’s principles are:

• Rice field soils should be kept moist rather than continuously saturated. This can minimise anaerobic conditions, as this improves root growth and supports the growth and diversity of aerobic soil organisms.

• Rice plants should be planted individually and separated by optimal spacing to permit the growth of roots and canopies, and to keep all the leaves photosynthetically active.

• Rice seedlings should be transplanted when young – less than 15 days old and with only two leaves – and also quickly, carefully and shallow, to avoid trauma to the roots and to minimise transplant shock.

(Cornell University)

Mayling Chan has been international programme director at Oxfam since 2013. She is the former CEO of Friends of the Earth (HK), East Asia representative of the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, and former programme director (Hong Kong, Mainland China, and international) at Oxfam. Chan was a lecturer at the City University of Hong Kong on development planning and analysis in 2011. One of her recent publications is “Unfinished puzzle, Cuban agriculture: The challenges, lessons and opportunities” (March, 2013, Food First, USA).

Mayling Chan has been international programme director at Oxfam since 2013. She is the former CEO of Friends of the Earth (HK), East Asia representative of the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, and former programme director (Hong Kong, Mainland China, and international) at Oxfam. Chan was a lecturer at the City University of Hong Kong on development planning and analysis in 2011. One of her recent publications is “Unfinished puzzle, Cuban agriculture: The challenges, lessons and opportunities” (March, 2013, Food First, USA).